Deep Wood Press is situated on four acres in Antrim County, surrounded by 450 acres of land under the protection and stewardship of the Michigan Nature Association. This is Chad Pastotnik’s home, backyard, place of work, and shelter from the storm of contemporary life. This maker of hand-built, hand-crafted fine press books, age 56, bought the property in 1992, built a book bindery, and began creating a life and vocation focused on making beautiful things. “Nobody knows who I am in the region,” he said. But in the arcane world of fine press books, it’s another story.

This interview was conducted in October 2024 by Sarah Bearup-Neal, GAAC Gallery Manager, and edited for clarity.

Pictured: Chad Pastotnik

Describe the medium in which you work. What is your work?

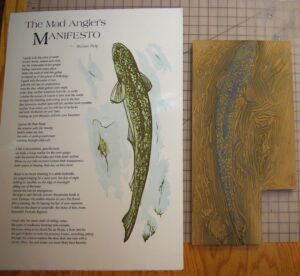

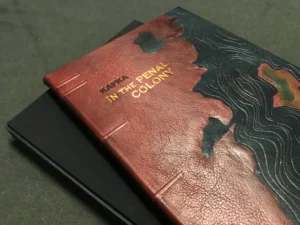

Private press books. The medium encompasses several disciplines: printmaking, bookbinding, designer bindings; the graphic arts of layout and design, and planning such things as books. It’s all done in-house, here [Deep Wood Press]. The type is cast on my linotype machine, in a separate building; brought over, proofed, corrected, printed onto fine, handmade papers from around the world, or specially made for the project at hand; the inclusion of original artwork; and then onto the bindery here. Basically, the only things that aren’t done here are making the paper and skinning the goats: That’s the primary leather we use for fine bindings. It’s traditional. Goat or calf [skin] are often used.

Is this a one-person operation? Or, do you have people who work with you?

It’s primarily me. I do take apprentices and students on occasion. On Tuesday, I have three of my former students and apprentices showing up to sew 60 copies of a book.

In your cosmos, is creating 60 books a big project?

It’s medium. My editions top out at 100 [books] these days. That’s primarily to expedite things. The bindery is the slowest process. Just staying under a certain number of books keeps me moving onto the next one.

Could you define what a fine press book is.

In modern meaning, it probably has its origins with the Arts and Crafts Movement. They brought back beautiful objects, and books were one of those things. Printing had become pretty well automated at that point, and book design was suffering greatly. Some interested individuals began promoting books beautiful once again, and presenting these kinds of editions — mostly classics on beautiful paper and well designed. So that tradition has carried forward into the 21st Century; but letterpress printing is no longer a viable, commercial entity, supplanted by computers and offset printing, and ink jet on-demand. Now it has become an even more specialized form of making books. I make books using pretty much the same practices as they did 150 years ago, and, essentially, the same forms as 500 years ago. Not much has changed here at Deep Wood.

I would imagine that when a fine press book is created, it’s usually not something like a Nancy Drew mystery; that the contents between the two covers have some special qualities, or are precious for some reason. Talk about that.

All the books I do speak to me in some way. Some of the books are definitely produced with some commercial ideas. All the books I do are on speculation. I don’t do much commission work. So if I commit two years of my life to a project, I have to have a pretty good idea that it’s going to sell. At the same time, for some of the smaller projects, I take on regional writers who aren’t necessarily known outside of my markets; but I still make the book because it has more meaning for me than a financial concern; the books I’ve done with Mike Delp, Jerry Dennis and Anne-Marie Oomen are all pure speculation. Most of my books are sold out pretty quickly, and they go to private collections around the world. As much as I love my regional writer friends, they’re not necessarily known outside of Michigan, the Midwest. So, name recognition with a book I’m pitching in England goes a long way. I’m at that happy point now where if I make it, they generally buy it.

Why do you think that’s true?

I’ve been doing this for 30 years, and I’m pretty good at it. I’m just lucky, I guess.

I can’t imagine there’s a lot of you doing fine press books.

Not a lot, no. I probably know most of them. We have a series of shows around the world that a lot of us travel to, giving the special and private collections people an opportunity to come to one place and do the hands-on thing. It’s an interesting group of people. There’s a lot of craft-centric parts to [bookmaking], so there’s a lot of people on that end. [On the other end of the spectrum] the book arts are now purely conceptual, and there are a lot of objects that sort of resemble a book.

When, and how, were you first introduced to this discipline?

Probably as an undergrad. I went to Grand Valley. And, [in the late 1980s] my professor [Delles Henke] had come from the University of Iowa, which has a long tradition of books arts. [Henke] showed us a couple of books he had done; but I wasn’t particularly interested in fine press then; The bookbinding part really intrigued me. At the time, I was doing really small engravings in copper, and they lent themselves to the book form. It wasn’t I until I got to be a better bookbinder that I wanted to introduce words. I found an old printer who was closing up shop on the northwest side of Grand Rapids, and he taught me some basics.

What draws you to the creation of fine press books?

I like being unique. There aren’t too many people who do it. I love the process — I’m a total junky for the process, the history, everything about books. The typefaces. The equipment. It’s the ultimate vehicle for information — or was for millennia. It’s all just beautiful. And the possibilities are unlimited. I could live five lifetimes, and still have things to learn.

What formal training did you have, specifically, for creating a fine press book?

None. I’ve done plenty of workshops through the Guild of Bookworkers, which is a national organization. So, if I want to learn a certain binding style, or leather tool technique, I can take a workshop. On the letterpress end of things, I did find myself in Iowa, not in a degree capacity; but I became friends with the people who were teaching the books arts there. Basically, I got a free education just for showing up. I got educated; but in indirect ways.

Describe your studio/work space you occupy.

There are 1 1/2 buildings devoted to it. The big intaglio press, and the typecasting are in a building 50 feet from here. The main studio is a building in two parts: half is the press room, the other half is the bindery, my office. It’s just full of stuff. In the early 90s, when I built the bindery part of the studio, print shops were giving away all the old letterpress stuff. They were making way for the new Xerox color printers and other things. Most of the stuff I got was free, for the cost of moving. It was the perfect time to get into letterpress because I was able to secure so much of this valuable equipment for little or nothing, and mostly from the region. The linotype machine came from Charlevoix where it used to make ballots, and newspapers. The only equipment I brought from a distance was a Little Giant [printing press] from a Carmelite Monastery in New Jersey.

I wonder if some of the people from whom you obtained your equipment scratched their heads and wondered, What’s up with this guy? He wants this old hunk of metal?

Certainly. The linotype machine guy said he’d deliver it to make sure he could get it out of his building.

Who typically comes to you wanting you to create a hand-printed, hand-bound book? And why?

Most of them are totally ignorant of the process. They don’t understand the costs involved. The other end of that spectrum is someone who does understand, and is still very interested in having their work produced. I’m finishing up a commission job at the moment. It’s 60 books, and it’s [the customer’s] second, fine press book. He’s got no wife, no kids, so he wants this to be his legacy. I don’t usually take this kind of commission work; but [the customer] was an exception. And, of course, anything Glenn [Wolff] and Jerry [Dennis] bring to me is instantly considered because it’s just so much fun.

People’s understanding of how books are created is now defined by different forces. You can push a button now, and have Amazon create, on-demand, 100 books in no time. Does that kind of understanding follow people when they come to you?

Even when you do books on-demand, you have to use their tools to do a little bit of formatting. I think there’s a big disconnect — I see this with a lot of young graphic designers; they don’t understand the process after it leaves their screen.

What’s your favorite tool?

Maybe my Vandercook press. There’s so little I ever need to do to it. It always gives me the results I’m looking for.

What tools do you use to make notes and record thoughts about your work?

I wish I were more organized; but usually it’s whatever scrap of paper is conveniently near. I’m organized enough that all those notes make it into one folder for each project — both for my own benefit, and I have places approaching me for my archive. I want things to make sense down the road.

Is this a personal archive? Or has the Smithsonian come knocking on your door?

U of M [University of Michigan].

Do they want your papers? And stuff?

Yes.

Did they tell you why?

I’m a Michigan Cultural Asset [a designation that comes out of the Michigan State University Michigan Traditional Arts Program.]

That must have blown your mind.

It’s nice to be recognized. I grew up in Cadillac. I’ve lived in Michigan my entire life; but nobody knows who I am in the region. Michigan’s institutions do collect me, so I’m grateful for that.

How often, in this day and age, are people recognized for doing hand work?

There’s the Traditional Arts Program at Michigan State. It’s geared toward craft — basketweaving, native dance, traditional instrument making; but they did award me a grant [in 2016]. Fine press books is one of those things that happily transcends both art and craft, or are equally represented in the end result.

When did you commit to working with serious intent? What were the circumstances?

Pretty much right away, when I bought the property and built the studio in 1992, and immediately began filling it with presses. That’s when I put the shingle out. A lot of the early work wasn’t fine books, but wedding invitations, and corporate print jobs. Soul-crushing work. They paid the bills. You pay your dues.

What made that work soul crushing?

Inevitably, working with people who don’t understand the process. Trying to make everybody happy. It wasn’t creative in any way. I was just a printer. I was also trying to sell my own art work; but at that time I was trying to sell locally. Engravings don’t sell very well in Northern Michigan. Not my stuff anyway. Focusing on book forms is what ultimately got me on the track I’m on. There aren’t any book shows in Michigan, so that forced me to go outside the state, and start taking workshops, and teaching.

What role does social media play in your practice?

I wish more; but I’m terrible at that stuff. My partner, Madeline, is the one who comes into the studio and takes pictures. Yes. I’m on Facebook, but I’m there for the friends’ kids. I don’t look at that stuff. I know it’s a powerful tool; but I guess, if I were hungrier, I’d exploit those tools more.

What do you believe is the visual artist’s role in the world?

I think the role of the visual artist is probably a purely selfish one. I think the role is just to make [the work]. That’s about it. It’s somebody else’s role to interpret it.

Not everyone agrees that the arts are an important part of being human, so the arts get scattershot support. You’re not turning out 2,500 widgets every day. You’re doing work that doesn’t necessarily yield a huge presence on the world. You’re living back in the woods in obscurity, and yet you have the audacity to think you should be doing, and you are entitled to do, creative work. With all that, how do you think about your role in the world as a visual practitioner?

I have a hard time with the commercial, established “fine art” world. Having achieved success [on his own terms, the fine art world] is a crock of shit. It really is. Most people don’t understand the processes anymore. That generation of people are dying, who grew up understanding this work. I struggle with this. I have a peer group, and I’m considered the socialist of the group. I’m the one who’s welcoming in the new people, trying to organize dinners, and group accommodations. That doesn’t go over well with the establishment sometimes, where they want to pick and choose who’s coming up.

To what degree do you feel that the creative work you do makes the world a better place?

The books are exquisite, if I do say so myself. A recent edition I did of The Winds In The Willows — I’d argue that that’s a book everybody should read. It’s not a kid’s book. And, our edition is exquisite. This is a book that will be around in 500 years; probably longer if taken care of. That’s a legacy. Books are something that tend to stick around. There’s more than one copy, so there’s a chance there’ll be a copy somewhere, in some collection, at some point. To whatever value that will have for the person pulling it from the stacks in 100 years, who knows? Each book I make — the subject matter and treatment — can vary widely. My collectors do appreciate the fact each book is a new exploration of a different process I know well. Keeping it fresh is important to me, as well. If I did the same thing for each book, it would no longer be art. That’s the fun part, coming up with the ideas, the artwork, and the design.

The books are exquisite, if I do say so myself. A recent edition I did of The Winds In The Willows — I’d argue that that’s a book everybody should read. It’s not a kid’s book. And, our edition is exquisite. This is a book that will be around in 500 years; probably longer if taken care of. That’s a legacy. Books are something that tend to stick around. There’s more than one copy, so there’s a chance there’ll be a copy somewhere, in some collection, at some point. To whatever value that will have for the person pulling it from the stacks in 100 years, who knows? Each book I make — the subject matter and treatment — can vary widely. My collectors do appreciate the fact each book is a new exploration of a different process I know well. Keeping it fresh is important to me, as well. If I did the same thing for each book, it would no longer be art. That’s the fun part, coming up with the ideas, the artwork, and the design.

How does living in Northern Michigan inform and influence your creative practice?

A lot of my books have to do with the natural world. Trees. Conservation. Water. Trout. Growing up and living in Northern Michigan has defined the work I do, and the projects I choose. The potential projects on the horizon — the Jim Harrison stuff, some more Hemingway perhaps — it’s all Michigania, the exploded version.

Did you know anyone, when you were growing up, who had a serious creative practice?

Not really. We had a good work ethic [in his family]. We were always helping somebody build a house. There was always a project at hand; but no musicians or artists to influence that kind of creative direction. From the time I was a kid, I knew that was what I wanted to do.

Why is making by hand important to you?

The craft aspect of the books, and in all art, has been neglected for 60 – 80 years in American art movements. I don’t think you can have successful art without successful craft. Craft just means you know your process, your materials, and you have a deft hand. I can show somebody how to make a book; but that’s just superficial — it’s just a blank book without contents. Right now, the emphasis in a lot of the arts is conceptual. It has a lot less to do with craft. It’s all about the idea part of it. As I alluded, the book arts have embraced that. You’re at a show, and the guy next to you has cranked out a book in a week on the ink jet [printer], and it’s selling for the same price point as something I’ve spent two years doing.

Your process is a hand process, and by design, it’s slow, it’s deliberate, it’s mindful. Why has it not been crushed by a world that is obsessed by speed?

Because books, whether or not you read them, are still revered by a lot of people. There is an undeniable history there that has shaped our world. Books are part of the public consciousness. In my case, it’s unique to make books the way that it used to be done, and I think people still value that. When they see the physical object, when they handle the book, and feel the materials, and see the presentation, it evokes a completely different reaction than you’d experience opening up a modern book in a book store. To open a book is intentional. Unlike a painting on the wall, the book is there on the shelf or the table, and to engage with it, you have to engage and use at least three of your senses to make that happen. I can’t imagine a world without books.

Do you have a library card?

Of course. Three. Two, local village cards, and one for the Traverse City library.

How do you feed and nurture your creativity?

That’s easy. I walk out the backdoor, and there’s every reason to be here in Northern Michigan. That’s one reason. The other end of it: I get to travel a fair amount now for work. My partner and I have a home in Avignon, in Provence, and I’m active with a foundation [the Foundation Louis Jou] over there. I get to see a lot of books, art, and beautiful places. I filter out the bad stuff, and keep all the good. Louis Jou is private press practitioner. In his lifetime, he produced 140 books, 90 of which were done on his iron hand presses, which I’ve now restored over there. My main connection with Jou is that he designed his own typefaces, which are exquisite. His studio was turned into a foundation, and I’m on that board, creating awareness of Louis Jou. I do projects when I’m over there, and bring in people to teach wood engraving, linocuts.

Read more about Chad Pastotnik here.

Sarah Bearup-Neal develops and curates Glen Arbor Arts Center exhibitions. She maintains a studio practice focused on fiber and collage.